5 Cards to Celebrate the Lad(d)s of Summer

Baseball is for the young at heart...or at least the young of name

Pete Ladd is no household name, even in baseball circles, but he does hold a place in the game’s history and the hearts and memories of certain baseball fans.

More on that in a bit, but first — Ladd would have turned 68 earlier this month, which put him on my radar, but he passed away last October.

That July birthday makes him the perfect impetus for this week’s baseball card cheese. So, with Ladd as our exemplar, here are five baseball cards that celebrate the “boys” of summer. It’s all right there in their names.

1954 Topps Junior Gilliam (#35)

One of my favorite baseball cards ever is the 1957 Topps Gilliam, which I wrote about once upon a time. But that one uses his given name — “Jim.” That won’t do here, since Jim is not an especially lad-like name.

But “Junior”? That’s the nickname Gilliam picked up while starring for the Negro National League's Baltimore Elite Giants before he landed with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Junior Gilliam definitely has a place on our team, and not just for his salad-days sobriquet.

As a rookie in 1953, Gilliam led the National League with 710 plate appearances and the majors with 17 triples. Add in 21 stolen bases and 125 runs scored, and it’s no surprise he won Rookie of the Year honors. The next year, Topps gave him the “Junior” treatment in their double-image base set.

(The one up there is actually from the 1994 Topps Archives reprints, so the dimensions are modern instead of 1950s oversized.)

Gilliam would go on to play 14 years for the Dodgers, accumulating nearly 1900 hits in the process. For his efforts, he ended up with four World Series rings — and, of course, a spot on our Pete Ladd squad.

1961 Fleer Schoolboy Rowe (#73)

Lynwood Thomas Rowe has a story that might sound a bit familiar to longtime Reds fans. Like the Ol’ Lefthander, Joe Nuxhall, Rowe found himself playing baseball with and against grown men at the age of 15.

While Nuxhall ended up with a place in history and a quick early bounce from the big leagues, Rowes payoff was a nickname that stuck — Schoolboy.

Rowe signed with Tigers just a year later, right before the 1926 season when he was still 16 years old. He wouldn’t make his big league debut for another seven seasons, but by then, “Lynwood Thomas” was a man-boy of the past, and Schoolboy was here to stay.

Good thing for Detroit, too, as Rowe won 62 games across his first three full seasons and helped the Tigers to American League pennants in both 1934 and 1935, winning the World Series in ‘35. After a few down-ish seasons, Rowe put up 16 wins as the Bengals nabbed another pennant in 1940.

There weren’t many baseball cards issued during the heart of Rowe’s career thanks to Depression-era materials shortages and a hobby still in its infancy. But he popped up on several cards issued after his career was over, like the 1961 Fleer deal above.

On pretty much all of them, he’s still “Schoolboy” — sort of ironic, considering he pitched in the majors until he was 39 and in the minors through age 41.

1970 Topps Coco Laboy (#238)

One of the first “old” cards I ever owned was a 1971 Topps Jose Laboy that I plucked from a quarter box at a flea market in 1984 or so. It seemed ancient, and I had to decide between Laboy and a few other guys I didn’t recognize, and at least one I did (Jim Spencer).

The last name cinched it for me, and that was before I knew about the “Coco” bit. That was/is a great card, showing Laboy in a faux fielding pose, but I like this one even better. There’s some irony in a shot of a .233 lifetime hitter mulling over which “weapon” he should use next.

Sort of like Telly Savalas deciding which hair gel to use for his next Johnny Carson appearance.

As the trophy on this card reminds us, though, Laboy had an auspicious start with the expansion Expos in 1969, smacking 18 home runs, driving in 83, and even hitting .268 as a rookie.

He was already 28 years by then, with a full ten summers of minor league seasoning under his belt. All of which must have made his name feel ironic, too, for those who were paying attention at the time.

1983 Fleer Pete Ladd (#37)

Our man of honor today, Ladd might not have even been an afterthought in baseball history had the Astros and Brewers not pulled off a minor October trade in 1981 — Ladd to Milwaukee in exchange for fellow righty Rickey Keeton.

Yawn.

Hardly anyone even noticed the deal until after the All-Star break in 1982, when the Brewers called up Ladd for his first big league action since a 10-game stint with the Astros in 1979.

Probably no one expected much.

And the lad Ladd debuted for the Brewers on his 26th birthday and made a total of 18 appearances down the stretch. His 1-3 record, 4.00 ERA, and three saves, were nothing special, but they were enough to make the Brew Crew’s postseason roster.

Good thing, too, because Ladd came up big (perfect!) in an epic five-game American League Championship Series against the Angels — three appearances, 10 batters faced, five strikeouts, no hits, no walks, no runs, two saves.

He made just one appearance in the World Series against the Cardinals, allowing no runs in 2/3 of an inning in a Game 2 loss.

That stretch in October was pretty much the high point of Ladd’s career, and he was done in the majors just a few months after his 30th birthday.

Still, no one could deny this Ladd had a good run.

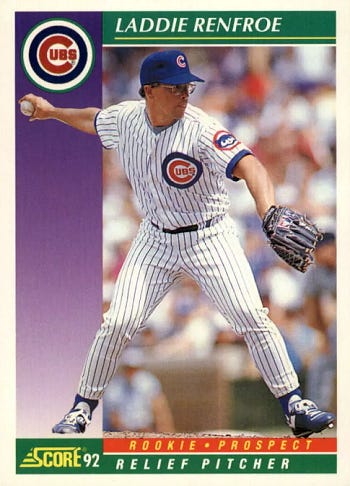

1992 Score Laddie Renfroe (#875)

The early 1990s Cubs were stuck in a run of 77-78-win seasons that felt pretty typical for the franchise — and that also made it easy to squint your eyes and accept “prospect” as it applied to their players without as much scrutiny as you might have applied to other clubs.

Seems Score took that approach when they included Laddie Renfroe as a “Rookie Prospect” in their 1992 high-number series.

Here was a guy who had been in the Cubs’ minor league system since 1984, mostly as a relief pitcher. He even popped off a remarkable 19-7, 3.14 ERA campaign in 1989 for Double-A Charlotte, making just two starts among his whopping 78 appearances.

After all that, Renfroe finally got the call to Wrigley Field in July of 1991, and he made four relief appearances between the third and seventeenth of that month. What no one didn’t know at the time was that he would never step on a big league mound again.

He would appear on that 1992 Score rookie card, though, a lad of a Laddie at a youthful 30 years of age.

—

All this kid talk has me feeling like a lad again. Or at least a Ladd.

Think I’ll go have a catch.

Thanks for reading.

—Adam

Sonny Siebert